Saturday, October 24, 2009

Fred York Pulaski County Poor Farm Superintendent

Tuesday, September 15, 2009

Who Killed Bonnie Huffman?

Who Killed Bonnie Huffman?

By Kristin Crowe, Associate Editor

On the night of July 2, 1954, a young, dark-haired schoolteacher known to be prim-and-proper left her friends and headed home shortly after midnight, but she never reached her destination. Searchers found her decomposing body in a road ditch 59 hours after she was reported missing. Her name was Bonnie Huffman, and her case is the oldest cold case in Missouri.

Bonnie left her Delta home on Friday, July 2, after telling her mother that she might spend the night with relatives in Cape Girardeau and not to worry if she did not come home. She lived with her mother and half-brother about 8 miles north of Delta, where she stopped at a gas station to buy a tire and call her friend, Mrs. Bess. The Besses met her at a movie in Cape Girardeau and afterward they all went to the Colonial Tavern to eat. Bonnie’s boyfriend, Doug Hiett, had broken up with her the day before, and Mrs. Bess said that she “had never seen Bonnie quite that upset before.” When Bonnie realized it was near midnight, she said she needed to go home. According to Sgt. Friedrich, the officer currently assigned to the case, the Besses tried to get Bonnie to stay with them. in Cape Girardeau, but she insisted on going home. Shortly after midnight she got in her 1938 Ford and started making her way toward Delta. The Besses just assumed she made it home, and her mother and brother assumed that she spent the night in Cape Girardeau. The truth—she did neither.

A person reported passing Bonnie’s empty car, which was sitting in the road with the lights on at 1:30 Saturday morning. However, no one reported her missing until mid-morning on Saturday. Bonnie’s half-brother Bobby Thiele found her car in the road about 8:30 a.m. Saturday on his way to Delta. He thought she must have had car trouble, left the car, and gone back to Delta, but the car started and he moved it out of the road. After checking with Hiett and calling the Besses, Thiele went home to tell his mother what he had found. Together, they went to Delta and called the police department in Cape Girardeau to report her missing. After an extensive search, the body was found at 9:00 a.m. on Monday, July 5, 1954, by a couple that noticed the smell. Her killer has never been found. The Delta Community has not changed much in the last 50 years, according to Sgt. Friedrich. The tight-knit community still talks about the murder, and it is as if the case never went away. Wanda Ross, Bonnie Huffman’s niece, has kept the case alive and in the forefront of people’s minds. If she had lived, Huffman would be around 73 this year, and the family would like to find closure.

At the time, there was much speculation concerning who committed the murder and how Huffman was killed, neither of which were ever positively determined. Some thought that Huffman’s boyfriend Hiett, who is still alive, committed the murder, but three other people verified his account of the evening. Many thought that she had been killed intentionally and then left in the ditch. Some speculated that the killer felt guilty and left her body where he thought it would be easily found, while others speculated that the killer placed the body there shortly before searchers discovered it. One of the primary tools investigators used to determine whether a person knew anything about the murder was the newly created polygraph machine. A 1956 article reported, “between 65 and 75 persons had been requested or had volunteered to take the [polygraph] test” in relation to the case. The police conducted many interviews and tried to ascertain whether the killer was someone Huffman knew or a transit visiting the area. The communities in the Delta area began collecting money for a reward soon after Huffman’s body was found. By July 14, 1954, The Southeast Missourian reported that someone had given or pledged $1340.75 to the fund, which would have been given to the person who provided information that led to the arrest and conviction of Huffman’s killer. Authorities eventually returned the funds to donors.

In 2004, an anonymous witness sent a letter to the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff’s Department detailing what he or she saw that night. Friedrich said the kind of information given in the letter could only have come from a witness. The person was coming home from a dance and came upon a car stopped in the road. There were two men in the ditch, and when the person stopped to see if they needed help, they tried to pull the person from his or her car. The letter writer managed to get away, but said that there was “someone in the Ditch hollering.” Friedrich said that the location the letter writer gave of the car is the same location Huffman’s body was found. The writer, however, has not come forward or given any other information. Friedrich (2007, March 12) said, “I don’t understand why they can’t come forward and give this family some closure. It’s the right thing to do.” However, he also admits that the writer may have passed away, as all suspects and people living at the time are either deceased or in their later years.

There are many aspects to this case that are not common knowledge. In 1954, police actually arrested a suspect. The Scott County Sheriff arrested Roy Wilson Jr., but the charges were later dropped. Many believe that this was a political move on the part of that county’s department used to garner attention. A psychiatrist determined that Wilson did not have the capability to perform the act of homicide and that his confession had been forced. Wilson later recanted his statement. According to the original officer on the case, Sgt. Percy Little, myriad rumors of how Huffman was murdered circulated in 1954, hampering the investigation from the start. Some of these rumors still persist today. The Southeast Missourian commented on these rumors: “Meanwhile, rumors all without foundation spread like wildfire over the weekend. How they started no one could tell.” Friedrich (2007, March 12) said that it “seems like that area was the wild west down there in the 50s,” with families and clans feuding against each other and trying to blame Huffman’s homicide on whomever they liked the least. There were rumors that she had been held in a cabin in the woods and that her body was carried in the trunk of a vehicle, but neither rumor had any substance. According to photographs, Huffman’s body was bloated around three times its normal size due to decomposition, and the ground beneath the body was reported to have been saturated with bodily fluids. Anything in which the killer(s) stored or transported the body would have contained physical evidence from the body, but investigators only found such evidence in the ditch. Recently, a man reported to the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff’s Department that he thinks his father committed the murder. The St. Louis man’s parents were from the Allenville community. When he was 7, he overheard his father and another man speaking, and the other man said to his father, “I think we should’ve shoved her up in the culvert farther.” However, there is no physical evidence, and both suspects are deceased.

The case proves frustrating to Sgt Friedrich for a variety of reasons, one of which is the case file, or lack of one. Only a single latent fingerprint taken off the rearview mirror has survived. No other physical evidence remains. The fingerprint did not lead anywhere when it was sent through AFIS, the Automatic Fingerprint Identification System. A “boatload of polygraphs” and seven or eight black-and-white photos still exist, but that is all (Friedrich, 2007, March 12). The Highway Patrol destroyed all other evidence in 1974, and the case information from which Friedrich is working is not the complete case file. Sergeant Little was called to the National Guard, leaving State Trooper Swingle to continue the case. Friedrich is working from Swingle’s paperwork. The case file tells who the officers talked to, but not why they chose to talk to each particular person. With so much information missing, Friedrich is unable to follow any sort of coherent thought pattern or evidence trail.

What Friedrich does have, though, is enough to posit a possible scenario. The coroner’s report states that Huffman died of a broken neck—“a displacement of the third cervical vertebra upward and to the left.” Huffman was 5 feet, 10 inches tall, weighed 133 pounds, and was very pretty by all accounts. Her good reputation was known throughout the area. Friedrich (2007, March 12) said that the 20-year- old, petite, attractive schoolteacher was known to be “a virgin—prim and proper.” The pathologist stated the following in the autopsy report: There is a single area of contusion and abrasion on the left side of the vaginal wall approximately 3 cm. within the vaginal canal. The speculum is introduced rather easily into the vagina. There is no evidence of a hymen and the introitus is intact with no evidence of blood or damage to the hymenal ring. (Lovinggood, 1954) While decomposition of the body prevents definitive proof the killers raped her, the contusion “suggests that rape was at tempted” (Friedrich, 2007, March 12). When searchers discovered Huffman’s body, the only article of clothing that was missing was her underwear. Her glasses, watch, necklace, and purse were missing, but she was still dressed in her dress, brassiere, and shoes when found. The physical evidence of possible rape, coupled with the missing underwear, provides a semblance of motive. The post-mortem changes and insect larvae on the body indicated that time of death was between 48 and 72 hours before the autopsy. In the autopsy report, the pathologist noted a “superficial abrasion over the left knee” (made before death) and the “dislocation of the 3 rd cervical vertebra and a dislocation at the left tempero-mandibular joint,” or a displaced jaw. There were no other wounds or broken bones. It appeared that Huffman’s killers forced her car over. People found her seat cushion and earrings scattered outside, indicating a possible struggle. Huffman left the car with the keys in the ignition, three-quarters of a tank of gas, and the running lights on. A toy gun was either in the car or in the road near the seat cushion and then placed in the car when Huffman’s half-brother moved the car off the road. Two different witnesses who saw Huffman driving home that night said she was alone. One passed her and saw her pass his house after he arrived home. He also saw “a two-tone green Chevrolet go northwest on the road at a very high rate of speed” shortly after. As the car reached the edge of town, the driver began blowing the horn steadily, which the witness said continued until the car was out of hearing distance. Within 15 minutes, the car came back through Delta, again traveling at a high speed.

The most plausible theory is that Huffman was driving home that night, and as she passed one of the taverns on her route someone noticed that she was alone. It was likely a crime of convenience, not premeditation. She had no known enemies and seemed to get along with everyone. The man (or men) followed her in his car, but allowed her to get a distance ahead of him. He then began honking his horn and sped up, attempting to get her to stop. Huffman stopped and the man drug her out of the car, leaving the keys in the

ignition and scattering the seat cushion and earrings in the scuffle. As he was trying to get her into his car, the letter-writing witness came upon the scene and was scared off. The man forced Huffman into his car and took off quickly enough to leave skid marks in the gravel. Huffman, trying to escape, opened her door and jumped out of the car, thus making the abrasions on her knees. The fracture of the third cervical vertebrae is result of “classical whiplash motion” from Huffman hitting the street. She was killed upon impact and the man sped off after realizing she was dead. At some point, he had attempted to sexually assault Huffman, possibly when the letter- writer came upon the scene.

There is one piece of evidence that has not yet entered this discussion of the case. A VFW magazine, American Legion, was found in the ditch in close proximity to the body. The magazine was the July issue and had been recently mailed to the address on the magazine, which was 150 miles north, in Saint Louis, MO. When police talked to the subscription holder, he admitted to being in Hiram, near the Bollinger-Wayne county line, over the Fourth of July to visit relatives. He had no reasonable explanation concerning why his magazine was found in the ditch with Huffman’s body. The man drove to the area from Saint Louis with his nephew, who says that his uncle then turned around and left that very day—a fact that leaves Friedrich suspicious. The magazine was “something that could have fallen out of the car if there was a struggle” (Friedrich, 2007, March 12). It was later determined that the nephew had raped someone in Bollinger County and had been placed in jail, casting even more suspicion on the uncle and nephew. However, the uncle was investigated and given a polygraph test, which he passed. Friedrich believes “they [police investigators] should have pounded on that and pounded on that.” The man is now deceased, leaving us wondering—was he the speeding man on the road behind Huffman that night? Was the uncle, or uncle-nephew team, responsible for Huffman’s death? Although the man passed a polygraph, Friedrich thought that the situation should have been more thoroughly investigated. While he readily agrees that the investigators at the time were “quickly over- whelmed” by the amount of information to be processed, Friedrich (2007, March 12) said that, as a new tool at the time, investigators “shouldn’t have used the polygraph as the sole tool to eliminate suspects; it is only as good as the operator.” Today, a well-done polygraph takes between three and four hours to complete, but some of the polygraphs given to suspects in the case took less than 40 minutes. As a new tool, it was somewhat unpredictable and the basic standards used to garner more accurate results had not yet been established. Another mistake investigators made at the time, Friedrich said, was to dismiss the case as just a disgruntled girlfriend who had run away. Huffman’s car was not processed for several days, before which her family was allowed to drive it home and let it sit for days in a dusty barn. Friedrich (2007, March 12) mentioned that, because the running lights were left on and the driver was missing, the investigators “should have taken greater care and processed the car.” A lack of manpower contributed to these and other such mistakes.

If the Huffman case had happened today instead of in 1954, Friedrich (2007, March 12) “would like to think we would have solved it.” Southeast Missouri has created a Major Case Squad that can be called in on special cases, contributing a vast amount of manpower and expertise to the specific case. Medical examiners now have better resources, and forensic knowledge has increased tremendously in the last 50 years. Additionally, all evidence is now run through the centralized database of the Highway Patrol, enabling crosschecking and cross-referencing between cases. The lack of preserved evidence and lack of a case file, however, continue to plague the Huffman case. Unless the missing glasses, necklace, watch, or purse are found, it seems unlikely that our improved methods will crack this case.

While he has gotten to know the family and would like to provide closure for them and the entire community, Friedrich (2007, March 12) said that the “chance he’s [the killer] still alive is slim to none.” Huffman’s killer was unlikely to be much younger than Huffman herself, meaning at the youngest he would be in his seventies. At this point, Friedrich’s hope is that the killer, if alive, will come forward, or that someone with information on the case, such as the letter-writing witness, will offer more information that could lead to answering who killed Bonnie Huffman?

References

Clues fade as hunt goes on for slayer of school teacher. [sic] (1954, July 10). The Southeast Missourian, pp. 1, 8. Lovinggood, T. A. (1954). Autopsy report: Miss Bonnie Huffman. Huffman Official Case File. Missing teacher found. (1954, July 6). The Southeast Missourian, pp. 1, 14. More cleared in slaying case. (1956, April 2). The Southeast Missourian, p. 1. No new clues at inquest into mystery killing. [sic] (1954, July 13). The Southeast Missourian, pp. 1, 4. Press hunt for killer in death of teacher. (1954, July 7). The Southeast Missourian, pp. 1, 12. Redeffer, L. (2004, July 6). Letter may be from witness to 1954 murder. The Southeast Missourian. Retrieved February 20, 2007, from http://www.semissourian.com/story/141049.html Remsberg, C. (1964, Summer). Schoolteacher murdered after the movies. Unsolved Murders, 30–37. Reward fund in slaying probe mounts to $275. (1954, July 9). The Southeast Missourian, p. 1. Reward grows in hunt for slayer. (1954, July 12). The Southeast Missourian, p. 1. Spur search for mystery killer. (1954, July 8). The Southeast Missourian, p. 1, 12. Why was body of slain teacher left by killer on public road? (1954, July 7). The Southeast Missourian, p. 1. $1340 reported in reward fund. (1954, July 14) The Southeast Missourian, p. 1.

Monday, September 14, 2009

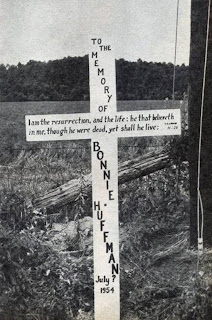

New Annonymous Memorial Cross for Bonnie Huffman

Huffman's niece, Wanda Ross, was 6 years old when her aunt was killed. She said the cross wasn't left by a family member but must have been put there by someone who knew specifics of the scene where her aunt's life ended.

Ross said the handmade cross was new but identical to one left at the scene 53 years ago. She said the new cross caught her family by surprise.

"My husband and I drove through there on Monday evening, and it wasn't there," she said. "Then when he drove through Wednesday it was there."

Huffman's friends and family have held several benefits to raise money for a reward for information leading to an arrest, conviction or resolution to her case. Ross said each benefit has resulted in a new lead.

"We had a candlelight vigil at the 50-year anniversary of her death," Ross said. "Then the sheriff's department got an anonymous letter."

The letter was sent anonymously to the Cape Girardeau Police Department, which forwarded it to the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff's Department. In the letter, the writer described a frightening encounter with two men the night Huffman disappeared on the same stretch of the highway where her body was found.

Last year's vigil in June was followed by another anonymous letter in the fall.

Last month, another benefit was held with a dance and silent auction to raise more funds for the reward.

"This time we got a cross," Ross said.

Although the cross was placed at the scene after the benefit, Ross doesn't think the same person who wrote the letters left the cross.

She said it was a kind thing to do, and the family would like the opportunity to thank whoever left it.

Ross also said she's unsure how long family and friends will continue to raise money for the reward fund.

"If there's no closure to this, we're going to make sure some kind of memorial is made for her later," she said. "But I feel in my heart that there's still someone out there who knows something about what happened to her -- and if someone saw something like that, I know they wouldn't forget it even in all this time."

According to Lt. David James of the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff's Department, last week's mysterious cross "does give us hope that someone has the information we need. What I don't understand is the hesitancy this person has to come forward. I can assure them complete anonymity. And even if they think they don't know enough to solve the case, they may have knowledge that is exactly what we need."

James asks that anyone with information call the department at 243-3551.

Bonnie Huffman's Cold Case Murder-2008 Update

By Bridget DiCosmo Southeast Missourian

For 15 years, what's left of the Bonnie Huffman homicide case file has sat in a cardboard box underneath Sgt. Eric Friedrich's desk in the criminal investigations office at the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff's Department.

Old, dog-eared police memoranda and dozens of yellowed polygraph transcripts are the only remaining keys to the unsolved murder.

Every few months, someone will call Friedrich offering information they claim could unravel the 54-year-old mystery of the young schoolteacher found curled up with her neck broken near an open culvert along Route N just north of Delta.

The ditch along Route N where Bonnie Huffman's body was found July 5, 1954. Photo from the files of The Southeast Missourian.

The ditch along Route N where Bonnie Huffman's body was found July 5, 1954. Photo from the files of The Southeast Missourian.Thursday marks the anniversary of the day Huffman's little 1938 Ford was found parked in the middle of Route N, six miles from her home, just two miles from the overgrown ditch where a strong odor alerted an Allenville couple to the site of her body about 60 hours later.

Since then, numerous suspects have been interviewed and many have died, yet authorities are no less mystified by the case, nor any closer to shedding light on what Huffman went through between the hours she left her home to see a movie with friends July 2, 1954, and the discovery of her body in the weeds.

Most recently, a Texas woman contacted Friedrich, saying she'd become aware that one of her late relatives, before his death in 1998, had confessed to the rape and murder of a woman near Delta, but like every other tip, proving it true seems nearly impossible.

Every time the case resurfaces in the media, the cycle repeats itself: A few tips will roll in, and Friedrich will drag out the box of aging documents and drop everything to run down the new lead.

But so far, nothing has panned out.

"We try to keep it in the news because you never know when that one's going to count," Wanda Ross, Huffman's niece, said Friday.

Like Friedrich, Ross knows the frustration of receiving vague tips from callers who won't identify themselves.

They usually say they know who did it but can't tell her, she said.

Ross has even tried listing her number in the newspaper, letting tipsters know they can call her if they aren't comfortable talking to police.

"None of the tips seem to hold any water," she said.

Still, when a "good, hot lead" does cross his desk, Friedrich says he'll chase it as far as it can go, but it does tend to get frustrating.

He still believes that a 2004 letter sent from Florida contained such detailed description that it had to have come from someone who had been at the scene of the killing that night.

The writer recalled driving back from a dance that evening and seeing a car stopped at the curve of Route N about a half-mile from Delta."Back then, people would stop to help someone. I did," the person wrote.

When the writer pulled over, two men began hollering for that person to get out, and one tried to grab the driver and pull them out of the car, the letter said.

"Why I tried to help I will never know, because without the help from God I would have been killed," the person wrote.

While the men struggled to get into the car, the person managed to get the clutch in and shift, only to have the two assailants rush to their car and try to block the road.

The letter included a roughly drawn but accurate map of the area near where Huffman's body was found. Friedrich noted that it had been mailed to 40 S. Sprigg St., the address of the Cape Girardeau Police Department, where Huffman's body was taken after its discovery.

Most of what was it the letter was "right on the money," Friederich said, including the fact that there had been a dance nearby in Ancell that night.

Now, four years after the letter worked its way to Cape Girardeau, the section of the sheriff's department Web site dedicated to the county's unsolved homicides reads "unknown from Florida, we received letter. Thank You. Please Call," with the promise of anonymity.

Just about every year, Friedrich has resubmitted a latent fingerprint found on Huffman's car to AFIS, the national database containing prints of convicted felons, but so far, like everything else in the case, no hits have been returned.

Bonnie's disappearance

Temperatures soared past 100 degrees the week Huffman vanished as a blistering heat wave blanketed Cape Girardeau.

Huffman left her mother's home in Bollinger County around 3 p.m. July 2, 1954, to see a movie in Cape Girardeau with Mary Lou and Cramer Bess, friends of hers who had recently gotten married.

The willowy brunette was 20 years old. She had just finished teaching her third term at Buckeye School near Old Appleton and was preparing to start an office job at the Missouri Utilities Co.

She and Mary Lou Bess had become close friends when Huffman taught Bess' younger brother in school, Bess said.

Douglas Hiett, Huffman's boyfriend of four years, had just returned from military service in Korea.

Though the couple was not officially engaged, Huffman had thought they would marry, but Hiett canceled their plans together that evening, and told her he wanted to break things off.

Huffman was upset and talked about Hiett a lot that evening, Bess recalled.

After the movie at the Broadway Theater, they'd gone to Wimpy's drive in to get a bite to eat, and stopped at Cape Rock to watch the barges float by for a while.

Then Huffman asked if they could drive past one of the taverns, near the bridge, presumably to see if Hiett's car was outside, Bess said.

"It used to be kind of a rough joint," Bess said.

Her husband would not let them go inside the bar, and they dropped Huffman off at her car, which she'd just gotten overhauled, Bess said.

"That was the last time I saw Bonnie alive," Bess said.

Huffman planned on spending the time in Cape Girardeau with her cousins, but they weren't at home, so she began the trek back home.

Around midnight, two people spotted her car rattling along Highway 25 at about 30 miles per hour. An hour and a half later, a driver saw Huffman's vehicle parked in the middle of Route N, and Huffman was nowhere in sight.

Bobby Thiele, her half-brother, and a friend were walking into Delta the following morning and saw Huffman's car.

At first, Thiele assumed the old beast had clunked out on her. But the keys were still in the ignition.

Thiele moved the car to a safer spot at the edge of the road, and as he did so, found a Gene Autry cap gun on the pavement near the car.

Authorities later theorized that the toy gun may have been used to threaten Huffman into getting into a strange vehicle. Chief Percy Little examined a toy gun that might have been used to stop Bonnie Huffman's car the night that she was murdered in July 1954. Photo from the files of The Southeast Missourian.

Chief Percy Little examined a toy gun that might have been used to stop Bonnie Huffman's car the night that she was murdered in July 1954. Photo from the files of The Southeast Missourian.

In 1975, highway patrol documents showed that most of the physical evidence in the case, including Huffman's clothing and the toy pistol, were destroyed, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported four years ago.

The location of Huffman's vehicle was strange enough that investigators, acting on the missing persons report filed by Huffman's mother, suspected foul play but didn't become certain until the body was recovered the night of July 5, 1954.

Only Huffman's Delta High School ring, inscribed with 1950, the year she'd graduated valedictorian of her class, and her initials, B.L.H., let authorities know that was the woman they'd been searching for.

The sweltering heat had badly decomposed the body. Though sexual assault was suspected, the autopsy results were inconclusive because of the decomposition.

Huffman's checkered shirt was torn, and her underwear, purse, white beaded necklace, watch and shell-rimmed glasses were missing.

The serial number of the watch is known and could provide a link to Huffman's killer if it were ever located, even after so much time has passed, Friedrich said.

Her neck had been broken at the third cervical vertebra, and her jaw had been dislocated.

Hundreds of tips poured in to investigators. Two grand juries examined the evidence in the case, and police conducted dozens of polygraph tests.

Percy Little, former Cape Girardeau police chief, who then investigated the case for the Missouri State Highway Patrol, called the case the most baffling he'd ever faced.

False confession

In 1956, Scott County authorities thought they'd solved the case when they obtained a partial confession from a Chaffee man who claimed to have known Huffman for several years.

"Bonnie was a fine good-looking girl, and I always wanted to go out with her, but I was afraid because she wasn't in my class," the man said in a statement taken by the Scott County Sheriff's Department.

The man claimed to have seen Huffman's car that night on Route N and bumped it several times from behind with his own vehicle, trying to scare her.

He finally forced her to pull over and made her get in his car, the statement said.

He began driving toward town because he wanted people to see them dancing together at the dance hall, but Huffman got scared and leapt from the moving vehicle.

After an hour of searching for her, he said he gave up and went home.

Scott County investigators issued an arrest warrant for first-degree murder for the man based on his statement, but after talking to the suspect, the highway patrol investigators handling the case dismissed the charges.

Police reports said he was of "such mentality that he would respond to a suggestion" and that the confession was "made entirely in response to suggestions rather than being volunteered on his own."

Cape Girardeau County Prosecuting Attorney Morley Swingle said the warrant would not have been valid anyway because an element of the crime would have had to occur in Scott County for them to make an arrest.

A second witness corroborated the man's statement, saying he drove Route N that night and saw the man intentionally bump Huffman's car, but that man was deemed mentally unsound after also describing seeing a submarine rise out of the river, according to police reports.

The arrest, though later unfounded, was the only one made in the 54-year-old homicide.

"If the opportunity ever comes along, we'll get it done," Friedrich said of the case, and wishes he could devote more time to it.

Swingle said the case has always been of interest to him because his father, the late Morley G. Swingle, was one of the original highway patrol investigators.

"I'd love it if it would get solved, but time is critical," Swingle said.

As more potential witnesses and suspects die with the passage of time, chances of solving the case may slip further away, Swingle said.

Ross said she knows there's a strong chance Huffman's killer may be dead but that deep down she doesn't believe that's true.

One year after Bonnie Huffman's body was found, a cross was anonymously placed at the location. Photo from the files of The Southeast Missourian.

One year after Bonnie Huffman's body was found, a cross was anonymously placed at the location. Photo from the files of The Southeast Missourian.Eighth Graders Take On Bonnie Huffman Murder Cold Case

Deanna Coronado

A group of inquisitive eighth grade students in Denise Yount's classroom at Gideon have been working on a classroom project investigating the 1954 Missouri cold case murder of school teacher Bonnie Loretta Huffman, talking to family members of the victim and making some of their own interesting and controversial discoveries along the way.

On July 5, 1954, 59 hours after her automobile was found abandoned in the middle of the highway not far from her home, a farm on the outskirts of Delta, Mo., where she lived with her parents Mr. And Mrs. Millard Thiele, police located the badly decomposed body of 20-year-old Huffman in a ditch on Route N, about one half mile northwest of Delta.

According to the newspaper reports detailing the nearly 53-year-old murder mystery, an autopsy performed on Huffman's body concluded that the nearly six foot tall brown haired, brown eyed Huffman sustained a fractured neck at the third cervical and that her left jaw was broken.

The autopsy also revealed that her knees were skinned and badly bruised and although the evidence could not prove that she had been criminally assaulted physically, the pathologist entered into his report that it was a probability.

The clothing and accessories that she had been wearing were reported as being missing from the location in which her body was found and were also not located in her car. The Missouri State Highway Patrol investigated the case, spending much of its efforts polygraphing suspects with inconclusive results. No one was ever charged in the murder.

The murder of the valedictorian of her graduating class in 1950, Bonnie Huffman would remain one of the, if not the single oldest cold case murder cases in Missouri's history.

According to Yount's students, the investigation into the murder they launched as a class project turned out to be one of the most interesting assignments they have taken on.

"This was a really neat project," said Brittany Campbell, a student who participated. "We really got excited about it because we actually got to talk to someone who was connected to the victim and knew a lot about the case."

The person Campbell was referring to is Huffman's niece, Wanda Ross of Allenville, Mo.. Ross was only 6 years old when her aunt was murdered.

The fact that people remember and new kids learn about the mystery encourages Ross, providing her with hope that her family that someone out there who knows what happened may yet come forward.

Ross visited with the students at Gideon and with KFVS channel 12 Heartland News to discuss the case and talk about what is still being done to find out more and determine who is responsible.

"We talked about a lot of details into the case and different theories that we and others have came up with. There is a lot of things about the case that just doesn't add up," said eighth grader Slayton Moody.

Moody and his classmates said that they also talked with Ross about a reward fund that has been created to help continue investigation efforts and solve the Bonnie Huffman Case.

According to the eighth-grade investigators, Ross said a bank account was established to build a reward fund for information leading to either an arrest of her killers or closure of the case.

"She hopes the publicity of the fund will jog someone's memory or tug at their conscience to do the right thing and call police," their teacher Denise Yount said.

Moody and others said that the project surrounding the murder mystery was so interesting mostly because it happened in Missouri and that Huffman was a teacher.

"The real-life aspect of it all made it so much more interesting than something we could just read in a book," another student, Dylan Cornett, added.

The students in Yount's class dug deep into the past uncovering newspaper articles, letters sent in from anonymous authors who claimed to witness the murder, and Internet articles following the case, providing a written look inside the murder and into the life of Huffman.

"Everything we have ran across in researching this case has only made us want to know more," eighth grader Tamara Shafer said of the experience. "From the beginning, when Mrs. Yount first told us about this story, we were all ready to get in their and investigate it for ourselves."

The students are even taking their efforts a step further by writing to humanitarians any anyone that they think could help. Students were in the talks to write letters to famously charitable people such as Oprah and Bill Gates.

"We just want to see if people who are in a position to help would be interested in helping with this case," Moody said. "I am thinking about writing Bill Gates a letter."

Gideon Principal Keenan Buchanan said that he supported his students' investigative research efforts and that he was happy to see all of the students so involved with the project.

"This is something that has certainly caught their attention and interests," Buchanan said. "I am glad to see them all learning through this project. Mrs. Yount and Mrs. Rudeseal have done an excellent job with these kids and keeping them involved."

Yount and fellow faculty member Sande Rudeseal have helped the students at Gideon gather a multitude of resources to be utilized in their investigation. Many of the students used the resources to also help them write a final thesis on the real-life murder mystery and tell what they thought about the case including their theories into the who, what, where, when and why's surrounding the case.

Family members and friends marked the 50th anniversary of the killing with a candlelight vigil and memorial service at the cemetery where Huffman is buried in 2004.

Today, they and others like the students at Gideon, still remember Huffman and continue to hope for more answers.

Anyone wishing to donate to the Bonnie Huffman Reward Fund can do so by mailing a check to the Bank of Advance at P.O. Box 400, Advance, Mo., 63730. Checks should made out to the Bonnie Huffman Reward Fund.

1954 Bonnie Huffman Unsolved Murder

Bonnie Huffman was a school teacher in Delta, Missouri and was found dead in a drainage ditch on Missouri Route N just outside of Delta, Missouri on July 05, 1954.

Letter may be from witness to 1954 murder

By: Linda Redeffer ~ Southeast Missourian (Reprint)

Fifty years ago on July 3, Delta schoolteacher Bonnie Huffman went to the movies in Cape Girardeau with some friends, then left them after midnight to drive home in her 1938 Ford.

She never made it.

Her car was found in the middle of Route N, keys in the ignition, half a mile from Delta, 6 miles from the home she shared with her mother and brother. On July 5, 1954, her body was found in a culvert about two miles from where her car was found. She had died of a broken neck. She was 20.

Huffman's murder remains unsolved. Like all unsolved murders, the case remains open because there is no statute of limitations.

Recently investigators came perhaps a little closer to solving the mystery.

Shortly after KFVS12 ran a recent segment on how investigative advances could have helped the Huffman case, the Cape Girardeau County Sheriff's Department received an anonymous letter that Sgt. Eric Friedrich believes may be from a credible witness.

"It had some information that I would think only a person who might have been in that area at that time would have," Friedrich said.

The letter is handwritten, has no signature and no return address other than Cape Girardeau, where it was postmarked.

Part of it reads: "I was driving back from a dance either Sat or Sunday night about 1 AM turned on Route N and a car stooped at the curve about 1/2 mile from Delta. Back then people would stop to help someone. I did.

"When I stopped 2 men came in a hurry and hollering what the hell are you doing, get the Hell etc. out, then I saw some one in the Ditch hollering. Why I tried to help I will never know because without the help from God I would of been killed. Because one of the men grabbed me and tried pulled me out of my car. I got my foot against the car-body, and my hand on the steering, my other hand was on the door handle, the other fellow was trying to get in the other door luck is that the door was locked.

"How I ever got the clutch in and shifted I will never know."

Fear of retaliation by Huffman's killers kept the writer from coming forward earlier, the letter said.

Friedrich said much in the letter matches other information he already has. He thinks this person may know more and hopes the writer will come talk to him in confidence.

In 1964, investigators tried to reach witnesses by releasing details of Huffman's murder to True Detective magazine, which published a story about the case.

Yet who killed Bonnie Huffman and why remains unknown.

'No place for us'

What is known is that the day before her murder, Huffman's boyfriend, Doug Hiett, had broken up with her. Huffman called her friend, Mary Lou Bess, suggesting they go to the movies.

"She was very upset," recalled Bess, who now lives in Perryville, Mo. "I had never seen Bonnie quite that upset before."

The two women and Bess' husband went to the Broadway Theater in Cape Girardeau. After that, Huffman said she wanted to drive by a certain tavern by the bridge because, according to accounts of that time, she thought it would be fun to watch the people going in and out. Some speculated she was looking for Hiett. Bess said that if that's what Huffman had on her mind, she didn't say it, but she thought it was unusual that her friend would want to go to that area.

"It was no place for us," Bess said. "I certainly would never get out or be seen in a joint like that."

Huffman also did not drive home on her usual route, accounts indicated. Investigators at that time speculated that she took a different route to pass by other taverns where she suspected Hiett might have gone. Hiett was among dozens of men questioned as a suspect at that time. He later was reported saying he regretted breaking up with Huffman and realized too late that he loved her.

"He has the feeling that if he had not broken up with her, none of this would have happened," Friedrich said. "He has a little bit of guilt."

Hiett is still alive but declined to be interviewed.

Sometime around 12:30 a.m. that night someone got Huffman to stop her car. A toy gun found at the scene led investigators to believe someone wielding it made her think it was real. She was apparently forced from her car and taken to another location and killed by a sharp blow that snapped her neck.

A police search turned up nothing, but a passing couple found Huffman's body in a ditch two days after she disappeared.

Because her underpants were missing, police think she may have been sexually assaulted; however, the body was too decomposed when it was found to be certain.

Suspects were questioned and polygraphed. Reward money offered eventually was returned to the donors. It yielded no results.

With a case half a century old, witnesses are becoming scarce. Cape Girardeau County Prosecutor Morley Swingle said it's possible Huffman's killer is still alive. People who commit murders are generally between 15 and 25, he said, leaving open the possibility that her killer is 75 at the most. Then there's the matter of 50 years of a guilty conscience.

"It's not unusual for someone who has done such a terrible thing, if he's getting closer to Judgment Day, to start feeling more and more guilty about it," Swingle said.

Looking for closure

Swingle, who has not yet seen the anonymous letter, said he has special reasons for wanting to prosecute Bonnie Huffman's killer. His late father was one of the Missouri State Highway Patrol troopers who worked on the investigation the year before Swingle was born. Swingle has read the entire file in the sheriff's department.

"It would be nice closure for me if I could have the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of prosecuting a case my father helped investigate," he said.

Huffman's family wants closure, too. Wanda Ross of Chaffee, Mo., Huffman's niece, is planning a candlelight vigil Saturday at Huffman's grave in Bollinger County Memorial Cemetery. She hopes someone will come who can answer a lifetime of questions.

Ross has grown up listening to rumors about who might have killed Huffman. After reading the anonymous letter, Ross said it firms up her belief that at least two men were involved.

Swingle said DNA evidence, unheard of then, could solve the crime now. He and Friedrich both said they have heard of killers who kept souvenirs from their victims. Such souvenirs could yield DNA evidence. No one has been able to find Huffman's watch, jewelry, purse, glasses and underpants. Someone somewhere might have something with Huffman's DNA on it, Swingle said. If that is the case, Ross said, the family would not hesitate to have Huffman's body exhumed for DNA testing.

Swingle said he wants the killer to know that the death penalty will not apply. It was in effect in 1954, he said, but its constitutionality was then under question. The most he can, and will, go for is life in prison.

After 50 years, the case remains a classic murder mystery.

"It's like picking up a book and reading halfway through," Friedrich said, "and the conclusion is missing."

Looney Vagrants in Cape Girardeau County

The negro is free in Missouri; but white slavery still exists in that commonwealth. A few days since there was posted on the courthouse at Jackson in Cape Girardeau county, this notice:

"Public Hire of Vagrants--Notice is hereby given that I, the constable of this county, will on January 12, hire out to the highest bidder, cash in hand, at the court house door in Jackson, the following vagrants for a term of six months: Tabitha Looney, aged forty-five; Barbara C. Looney aged eighteen, and Fanny Looney, aged twenty.

(Signed) "Henry D. Loomis, Constable."

The local paper says of the sale that followed: "The above notice drew quite a crowd to the court house steps in Jackson to-day. The vagrants were brought to the front one by one and their services auctioned off. The crowd and the manner of the auctioneers savored of the days of slavery, but the bidding was not as brisk as it used to be in those times. The oldest vagrant's services were not in much demand, and were taken for $12. Barbara brought $18, and Fanny $24."